The M’Chigeeng First Nation is an Ojibwe First Nation group located on Manitoulin Island between Lake Huron and Georgian Bay in Ontario, Canada. Over a decade ago, they established a vision for self-sustainability with renewable energy generation. This led the M’Chigeeng First Nation to install two wind turbines. Although the wind turbines supply energy to the Ontario grid under a Feed In Tariff (FIT) contract, the quantity of energy produced roughly equals the current annual energy demand of the community.

(M’Chigeeng Wind Turbine)

(David Suzuki in 2012 at Wind Turbine Opening Day Celebration)

The Community is now exploring net-zero housing options. A net zero dwelling by definition has very low energy consumption by virtue of superior thermal insulation and advanced construction techniques, and it is capable of producing as much clean energy as it consumes using onsite renewable energy generation sources such as wind or solar generation systems. According to Natural Resources Canada, a Net Zero dwelling is expected to be 80% more energy efficient than a new building constructed to today’s building code minimum standards.

Converting indigenous communities to net-zero housing can address the pressing issue of climate change by reducing carbon emissions and promoting energy efficiency, plus it can serve as a powerful tool for addressing energy poverty and under-employment within indigenous communities. It can also trigger rethinking the concept of indigenous villages and revitalize cultural traditions and foster community resilience.

YellowYellow was engaged to provide guidance on how they can reduce their environmental impact through transportation. We are excited to share the results of our research which explored the impact of the transition from internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles to electric vehicles (EVs) from both a financial and emissions perspective.

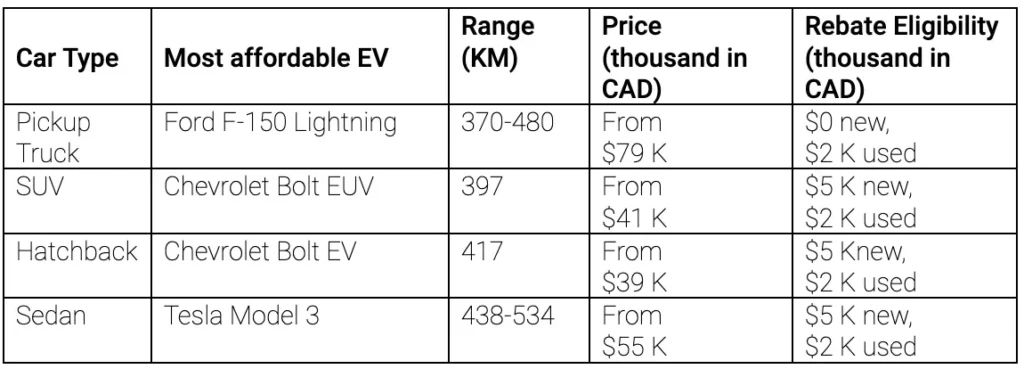

To begin, we compared the EV options available in the Ontario, Canada market. We identified the least expensive vehicles within four main car types: pickup trucks, SUVs, hatchbacks, and sedans. We also factored EV rebates from the government into the analysis.

The financial cost of replacing M’Chigeeng’s population of hundreds of vehicles, given the preference for strong pickup trucks, was estimated to be approximately $40 M (or ~$ 80K dollars per vehicle). This includes the cost of installing level two EV chargers. To reign in the costs, a further analysis could explore alternate scenarios, including the purchase of used EVs, modifying the proportion of pickup trucks, and exploring other rebates and grants available to Indigenous communities.

While the capital expenditures are high, the operating expenditures are lower than the current state. We found that an EV transition could save the M’Chigeeng First Nation $1.4 M each year on gasoline as well as $200 K each year on maintenance. This includes the cost of EV charging and works out to an average annual savings of $3 K per vehicle.

Following the cost analysis, we conducted a life cycle analysis (LCA) to understand the total emissions. The production of each new electric vehicle is expected to emit approximately 8 tonnes of CO2. This means that a total of 4,000 tonnes of CO would be released if all 500 vehicles were replaced by EVs. However, due to the relatively low emissions associated with Ontario’s power grid, which generates 93% of its electricity from non-emitting sources (mean emissions of 25g of CO2 per kWh), and the reduction in gasoline consumption, it was estimated that this EV transition would lead to an annual emissions reduction of ~2,400 tonnes (equivalent to 4.8 tonnes per vehicle). In less than two years, the transition from ICE vehicles to EVs allows for net carbon negative.

The final piece we considered was the potential for “range anxiety” due to the transition to EVs. Historically, there has been a backlash to EVs due to the relatively low range they are able to drive, and the relatively high amount of time it takes to charge them. However, with modern battery technology and the growing charging infrastructure in Ontario, this is becoming less of an issue. In fact, each of the vehicles analyzed has a range large that is capable of commuting to and back from Sudbury. This is the nearest large city where many members of the M’Chigeeng First Nation work. Additionally, there are many available public chargers between the M’Chigeeng First Nation and Sudbury to help further reduce the risk of running out of power while traveling.

To augment our research, we proactively explored EV charging infrastructure, pinpointing distinct options and potential funding opportunities. We proactively engaged with leading regional EV charging providers to assess their offerings and explore incentive-based funding. During these discussions, we discovered a partnership opportunity with another community that was also looking to build EV infrastructure, further enriching our planning strategy.

The M’Chigeeng First Nation community is located on Manitoulin Island, between Lake Huron and Georgian Bay. The current EV charging infrastructure (bolts in yellow) is in the Sudbury area.

Despite the initial financial cost to the M’Chigeeng First Nation, transitioning to EVs would save them significant amounts of money each year, while significantly reducing their environmental impact.

Ultimately, if they can successfully find ways of reducing the initial vehicle transition costs, an EV transition project could be a tremendous win for their community. It could in fact serve as a model case for communities across Canada.

Our comprehensive analysis extended beyond housing to encompass the broader environmental and economic implications of an EV transition. This First Nation Community stands as a testament to the transformative power of visionary thinking and sustainable action. With a clear environmental and business case established for both net-zero housing and transportation, the community leaders, equipped with our insights, are now actively exploring funding solutions to bring these ambitious projects to fruition.

Ready to Transform Your Community’s or Company’s Future? Connect with YellowYellow today and embark on a journey towards a sustainable tomorrow. Should you have any questions about this research or need support with your transition to net zero, please don’t hesitate to contact us at hello@yellowyellow.ca.

Kaitlyn D’Lima holds both a Bachelor of Business Administration and a Master of Science and Sustainability Management degree from the University of Toronto. She is also trained in greenhouse gas (GHG) accounting.

She brings extensive experience in sustainability and business transformational projects. She is known for her ability to execute projects of any size with both urgency and accuracy. Kaitlyn has a natural talent for improving stakeholder engagement. She’s a real trailblazer when it comes to benchmarking and research.

Kaitlyn is a runner who participates in outdoor adventure races.

Arun B Pazhayannur holds a degree in mechanical engineering and is a Chartered Accountant. He also has an MBA from the Ivey Business School at the University of Western Ontario. Along with his academic achievements, he has a thorough knowledge of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) principles, which he incorporates into his consulting work.

Arun is well-known for his leadership abilities as well as his strong skills in data analysis, financial modeling, and operations management. He has been recognized for his ability to identify practical solutions and deliver value to clients ranging from banks to payment companies to software providers. Arun is also a past President of Toastmasters Club.

In his free time, Arun enjoys scuba diving.In his spare time, Arun likes to scuba dive.

Gregory Donovan is a Chartered Accountant. He is a Fundamentals of Sustainable Accounting (FSA) Credential Holder. He obtained an Honours in Business Adminstrations (HBA) from the Ivey Business School (Western University) and a Master or Laws (LLM) from the London School of Economics. Gregory is the CEO of Avondale Private Capital, a sustainable finance firm focused on energy transition finance and carbon markets. He has presented on these topics at conferences in Canada, the US and UK.

Greg participates in the occasional triathlon and loves to go skiing and sailing with his two young children.

Margaux Loptson holds a Bachelor of Arts (Psychology) and a Bachelor of Arts (Criminology) from Pennsylvania State University. In addition, she holds several research certifications, including Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans.

She has been an essential player in AI-powered teaching and learning projects as a User Experience (UX) lead. Margaux is known for applying her design thinking, problem-solving and analytical skills to make a positive impact. She is a native French speaker.

Margaux is a fitness enthusiast who can be found hiking around Central Park in NYC.

Ritika Jain holds a Masters in Environmental Sciences, Policy and Management from Lund University (Sweden) and a Bachelor of Technology from Indraprastha University (India). As a lifelong learner, she is pursuing a Graduate Diploma in Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability at the University of Toronto.

Ritika is a recycling and responsible supply chain specialist. Through her work, she collaborates with organizations to implement circular economy focused policies to ensure compliance with regulations.

Her proficiency in data analytics and with the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) enable her to manage complex sustainability data. Ritika also volunteers with the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network, engaging with youth to drive positive change.

Ritika is a native Hindi speaker. She is a certified hiking leader who enjoys travelling.

Jonathan Spence holds an Honours Bachelor of Integrated Sciences (Earth and Environmental Sciences) from McMaster University and has his certification in Geographic Information Sciences from the ESRI Canada Center of Excellence at McMaster University. Jonathan worked as a research analyst in the environment and sustainability group for a TSX listed company.

He is pursuing his Ph.D. in Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Alberta, where he is researching the development of carbon capture techniques and their applications to the mining industry. Jonathan is focused on helping companies to minimize their carbon footprint while supporting their economic growth.

Jonathan is an avid water polo player and coach. He plays for the local National Championship League team.

Gurnoor Gandhi holds an MBA from Ivey Business School (Western University) and a postgraduate diploma in Maritime Energy Management (Sweden). Gurnoor brings experience with sustainability frameworks including TCFD, GRI, and CDP and is pursuing FSA credential (SASB).

Gurnoor has global leadership experience in the shipping industry managing assets worth millions of dollars on the high seas and has led diverse teams worked in Monaco, Singapore, and India. Most recently, he led organizational development and client partnerships at CARD, a non-profit focused on rural development and renewable energy.

Gurnoor brings a blend of technical and leadership skills. He applied his knowledge of greenhouse gas accounting and carbon capture to support clients with niche energy transition projects. He is known for putting his problem-solving, stakeholder management, and project management skills to work to help firms expedite their ESG Journey.

Gurnoor is a certified BMW adventure motorcyclist who finds off-road rides rejuvenating for body and spirit. He enjoys hiking with his family.

Lisa Annabel Ellis holds an Honours Bachelor of Science (Environmental Science) from the University of Toronto and an MBA from the Ivey Business School (Western University). She is a certified Project Manager Professional (PMP) with a Six Sigma Green Belt. Lisa is a Fundamentals of Sustainable Accounting (FSA) Level II Candidate. Applying her deep expertise in business and operational strategies, she has led award-winning transformational initiatives.

Drawing on her well-rounded science and finance expertise, she launched YellowYellow to help clients advance their sustainability practices. As an advocate of transparency and good governance, she partners with clients to understand their risks and opportunities to generate superior long-term value. Stakeholders across the value chain recognize the impact of this effort. She has been called upon to be a keynote speaker and lecturer.

Lisa is an advanced scuba diver who enjoys most water-related sports.